Doug Tallamy knows the importance of small things, like caterpillars. Doug’s a writer, entomologist, and is an expert on biodiversity and wildlife. His talk at the Toronto Botanical Garden was entertaining and informative. It was also heartbreaking.

Nature lovers (like me) love feeding the birds. I buy those big bags of birdseed. It’s fine to do this, especially in the spring when natural food sources are scarce. But it’s very far from the whole picture. The missing piece is baby birds. In spring, birds raising their broods have nests full of them, with mouths wide open. A baby bird can’t eat bird seed: they need caterpillars. And birds spend all their time collecting huge numbers of caterpillars for their hungry babies. Oddly, in all the backyard bird books—and I’ve read a few—I can’t recall seeing anything about the importance of caterpillars. I guess it takes an entomologist. And as Doug showed us, no caterpillars, no chickadees.

Doug Tallamy told the story of how a brood of chickadees died in the nest because there weren’t enough caterpillars in the area to feed them. Studying the nest where the baby birds died, they found uneaten sunflower seeds, inedible to baby birds. It’s one of the most tragic stories I’ve ever heard.

Caterpillars are good food for baby birds because they are soft, full of nutrients, and can be easily shoved down the bird’s throat. Why would there be no caterpillars for this nest? Well, the caterpillars didn’t have the leaves they needed from the right tree. No caterpillars, no chickadees.

Plant-Insect Relationships

We learned from Doug a key thing: evolution has created plant-insect relationships. Insects, (and insect larvae) have evolved together with specific trees and plants.

Doug: “Certain caterpillars need specific species to feed on when young. They specialize on only a few types of plants. 90% of the insects that eat plants can develop and reproduce only on the plants with which they share an evolutionary history.”

All plants leaves have poisonous substances protecting them from predators; however certain caterpillars have evolved alongside those plants, and can safely eat the leaves. It’s a symbiotic relationship. The tree’s leaves may get a few holes, but they can spare it, and the birds get a nice meal via those well-fed caterpillars. Not only do the birds need the caterpillars for the baby birds, but they eat the mature insects and moths as well. We think of hummingbirds mostly living on sugar water and nectar, but insects are a huge part of their diet as well. And an insect diet is important for all songbirds.

Nature lovers get excited by looking at butterflies and moths. But all those butterflies come from larvae, otherwise caterpillars. They aren’t just a sideshow, but are relevant to the main event. Doug tells us “A world without insects is a world without biological diversity.” The focus on caterpillars is what makes a Doug Tallamy lecture special, as well as a visual treat. He has a dizzying array of fascinating photographs of caterpillars. And knows the names of all of them.

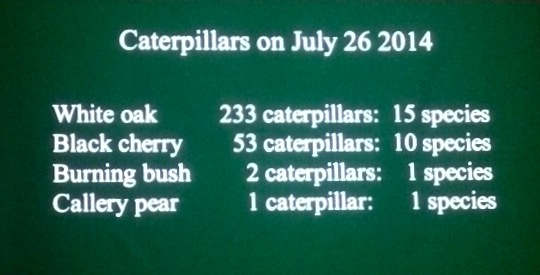

Part of Doug’s research involves counting caterpillars among trees to determine how useful any tree species is to what he calls ‘the food hub’. That’s how he assesses how well any section of garden supports wildlife.

A large tree in the landscape, like an oak, supports hundreds of species. As Doug says “They give up a few of their leaves for the caterpillars to munch on. But the tree still stands and flourishes. It can spare those leaves.” Some trees, popular with homeowners, ginkgo, for example host nothing. Think of that: Nothing. He compares these attractive, yet sterile, trees to statues in the garden. Have one maybe, but don’t build your whole yard around them. Focus on planting trees that sustain wildlife, and white oak in particular. Black cherry is the next best. He mentions you can grow an oak from an acorn for free. He’s done it.

Another point Doug makes is that most people think that our wild areas like parks and conservation areas are enough to keep nature flourishing. But it’s really not enough area to sustain nature. Doug tells us, “430 species of North American birds are at risk of extinction.” There are 50% fewer songbirds today compared to 40 years ago. We need to move wild areas into the places we live, the cities and suburbs.

“And not only are viable habitats fragmented, they have also been invaded by 3300 species of introduced plants, many of them invasive.”

What we really need are connected areas of wildlife so that creatures can travel and source enough food for survival. If homeowners move away from the traditional lawn, and decorative (sterile) tree habit and plant trees with food hubs, birds and insects will survive. Even foxes, skunks, and other wild mammals need insects and caterpillars to live. Our planting choices are hugely important. He bemoaned his neighbour’s choice of planting Callery pears: thirty-six of them. Yeesh. They are pretty in flower in spring, but Callery pears offer nothing for wildlife, and they also have an invasive habit, spreading into nearby fields.

Saving Nature By Accident – The Atala Butterfly Story

The situation is really dire, and in the case of dead baby birds, it’s heartbreaking. Doug does have hope, however, that we can change and swing the trend towards more biodiversity. One of his most heartening stories was about a revitalization that came about unintentionally. A community in Florida accidentally brought back the endangered Atala butterfly. The larvae of the butterfly needed a particular palm for food, the coontie palm. However, this palm had been harvested out of existence when it was discovered it could be used as an edible starch. No one had seen this particular butterfly for a long time and it was presumed to be extinct. In recent years, landscapers had re-discovered this native coontie palm, and started using it widely in their plantings. It became very popular. Lo and behold, the once extinct Atala butterfly returned. It turned out, it hadn’t gone extinct, but there was a tiny population that had been hanging out in the Florida Keys. Once their food source became plentiful again the butterflies repopulated and spread out. Doug says if a species can be rescued by accident, what could we do by planting landscapes that sustain wildlife mindfully.

I want to get planting as many white oaks as I can now. Doug stresses that you don’t have to have a garden with only natives, but keep your balance towards native plants that sustain biodiversity. His researchers contributed to a database of native plants hosted by the National Wildlife federation. It’s US based, but keying in a Zip Code close to Toronto, (like Buffalo) will give you appropriate plants for our region.

To read more about Doug’s work, check out his book, Bringing Nature Home.

1 comment

I’ve loved his talks and always go away feeling happy that I have oaks, hickories and elms in my garden….and of course wildflowers.